The amount of methane formation per unit of ingested feedstuff can differ significantly between individual animals as it is a heritable trait ( 16). Thus, the H 2 concentration stays constant, although its consumption by methanogens is partially inhibited in the rumen. Already a small increase in the H 2 concentration ( 8) leads to both down-regulation of H 2-generating pathways ( 12) and up-regulation of H 2-neutral and H 2-consuming pathways such as propionate formation, resulting in additional energy supply to the host animal ( 13– 15). The H 2 concentration increases substantially only when methane formation from H 2 and CO 2 is specifically inhibited by more than 50% ( 10, 11). Because at 1 µM, H 2 formation from most substrates in the rumen is exergonic ( 9), the low H 2 concentration indicates that H 2 is consumed in the rumen by the methanogens more rapidly than it is formed by other microorganisms ( 10). However, the methane eructated by ruminants contains only minute amounts of H 2 the concentration of dissolved H 2 in the rumen is near 1 µM ( 8), equivalent to a H 2 partial pressure of near 140 Pa. It is formed by methanogenic archaea at the bottom of the trophic chain mainly from carbon dioxide (CO 2) and hydrogen (H 2) ( Fig. Methane (CH 4) formation is the main H 2 sink in the rumen.

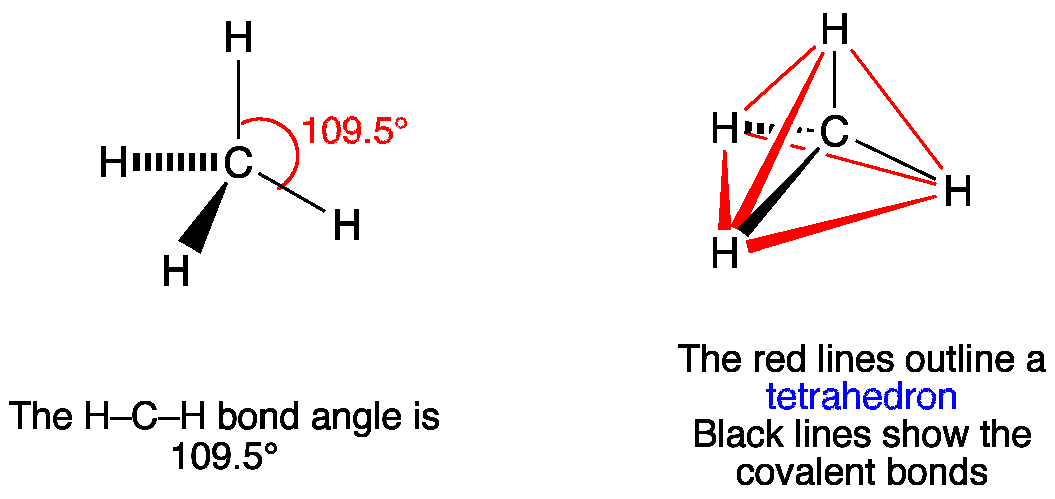

Using pure cultures, 3-NOP is demonstrated to inhibit growth of methanogenic archaea at concentrations that do not affect the growth of nonmethanogenic bacteria in the rumen. Concomitantly, the nitrate ester is reduced to nitrite, which also inactivates MCR at micromolar concentrations by oxidation of Ni(I). With purified MCR, we found that 3-NOP indeed inactivates MCR at micromolar concentrations by oxidation of its active site Ni(I). Molecular docking suggested that 3-NOP preferably binds into the active site of MCR in a pose that places its reducible nitrate group in electron transfer distance to Ni(I). The nickel enzyme, which is only active when its Ni ion is in the +1 oxidation state, catalyzes the methane-forming step in the rumen fermentation. We now show with the aid of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo experiments that 3-NOP specifically targets methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR). Therefore, our recent report has raised interest in 3-nitrooxypropanol (3-NOP), which when added to the feed of ruminants in milligram amounts persistently reduces enteric methane emissions from livestock without apparent negative side effects. Along with the methane, up to 12% of the gross energy content of the feedstock is lost. Whereas the short fatty acids are absorbed and metabolized by the animals, the greenhouse gas methane escapes via eructation and breathing of the animals into the atmosphere. A constant charge density at the F sites and a monotonous decrease in the C–F bond distance as n increases account for this variation.Ruminants, such as cows, sheep, and goats, predominantly ferment in their rumen plant material to acetate, propionate, butyrate, CO 2, and methane. The maximum in the experimental dipole moment of the fluoromethanes at n=2 is explained by a point-charge approximation. Decoupling these two influence parameters is the prerequisite to elucidate their role in directing rehybridization on the central carbon and the terminal halides. In this context, we have decoupled the influence of a variation in n and changes in the bond angles on charge distribution at the C and F sites. We find a correlation between the hybridization on the central atom and the terminal atoms. Intra-molecular interactions between the H and F sites are proposed as one of the reasons for the large H–C–H bond angle in CH 2F 2. The electrostatic attraction between the central carbon and the terminal sites and the repulsion between the terminal sites compete in their influence on the molecular geometry. Factors influencing the geometry of these molecules, which have not been considered hitherto, are discussed on the basis of ab initio molecular orbital calculations using natural bond orbital analysis.

Ch4 molecular geometry series#

A qualitative rationalization of the structural anomalies in the series of halomethanes, (CH 4− nX n n=1–4, X=F, Cl, Br), is presented.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)